- Home

- Ultra Violet

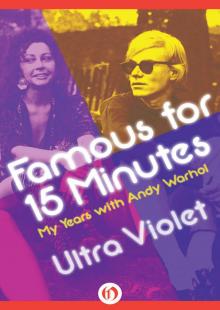

Famous for 15 Minutes

Famous for 15 Minutes Read online

EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

BE THE FIRST TO KNOW ABOUT

FREE AND DISCOUNTED EBOOKS

NEW DEALS HATCH EVERY DAY!

Famous for 15 Minutes

My Years with Andy Warhol

Ultra Violet

Contents

Dramatis Personae

Memorial

The Factory

Entourage

Blow Job

Andy’s Beginnings

Isabelle’s Childhood

Escape from France

The Dali Years

Ultra, the Girl in Andy Warhol’s Soup

Pop Art

Rock Beat

Underground Hollywood

High Living

Transvestites

24 Hours

Julia Warhola

Chelsea Girls

Sex?

The Shooting

Recovery

Valerie Solanas

Parties of the Night

Moonstruck

Edie

In Love

Reform or Perish

Home, Sweetest Home

The Sobering Seventies

Survivors

Andy’s End

Mass

Postmortem: The Kingdom of Kitsch

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Disclaimer

Just as Impressionist painters used strokes of color rather than photographic techniques to portray objects, so I have taken artistic license in conveying both reality and essence in this book. I have relied on memory, diaries, tapes, recorded phone calls, press clippings, books, magazines, interviews, and conversations to document what I bear witness to. All conversations are reconstructed and are not intended, nor should they be construed, as verbatim quotes.

Dramatis Personae

THE STARS

Ultra Violet

Andy Warhol

SUPPORTING CAST

John Chamberlain

John Graham

Salvador Dali

Edward Ruscha

THE FACTORY ENTOURAGE

Tom Baker

Gerard Malanga

Brigid Berlin (Polk)

Taylor Mead

Jackie Curtis

Paul Morrissey

Joe Dallesandro

Billy Name

Eric Emerson

Nico

Andrea Wips Feldman

Ondine

Pat Hackett

Lou Reed

Baby Jane Holzer

Edie Sedgwick

Fred Hughes

Valerie Solanas

Ingrid Superstar

Velvet Underground

International Velvet

Viva

Jed Johnson

Holly Woodlawn

CAMEOS

Cecil Beaton

John Lennon

Betsy Bloomingdale

Liberace

Maria Callas

Charles Ludlum

Truman Capote

Norman Mailer

Divine

André Malraux

Marcel Duchamp

Max’s Kansas City (Mickey Ruskin)

Bob Dylan

Jim Morrison

Ahmet Ertegun

Tiger Morse

Mia Farrow

Si Newhouse

Jane Fonda

Barnett Newman

Miloš Forman

Richard Nixon

Princess Ira von Furstenberg

Rudolf Nureyev

Greta Garbo

Aristotle Onassis

Judy Garland

Yoko Ono

Princess Grace

Lester Persky

Jimmy Hendrix

Pablo Picasso

Freddy Herko

John Richardson

Dustin Hoffman

Robert and Ethel Scull

Howard Hughes

Frank Sinatra

George Jessel

Sam Spiegel

Janice Joplin

Jon Voight

Robert Kennedy

Duke and Duchess of Windsor

Timothy Leary

Andrew Wyeth

Shoot ’em up (David Gahr)

And a good time was had by all: the Factory, 1968 (David Gahr)

MEMORIAL

April 1, 1987: I am apprehensive about attending the memorial service for Andy Warhol at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. A month earlier, the Star, a gossip magazine, ran my photograph with the recklessly erroneous caption: “Valerie Solanas got her moment in the spotlight when she burst into Warhol’s studio and shot him.”

I never shot Andy. That was Valerie, a passionate revolutionary, who was sentenced to three years in prison for her crime. I am worried that today an Andy-worshiper may recognize me from that picture and take misguided revenge. Or the opposite may happen: A furious, still crazed Warhol acolyte, carelessly discarded when the master grabbed all the fame and money, may throw a bomb in the cathedral to commemorate a final happening on this April Fool’s Day.

In death, as in life, Warhol deals in contradictions.

Outside the steps of the cathedral, a woman is shouting, “The monster is dead! The monster is finally dead!” I wonder: Did this woman have a grudge against Andy? Or is she trying to become famous for fifteen minutes?

What kind of mass can you put on for Warhol? Will the Warhol public be more at ease with a black mass?

His Eminence John Cardinal O’Connor has declined to celebrate the mass. Is it in fear of turning St. Patrick’s into a cathedral of sinners? Or to avoid being reminded of a priest’s recent death from AIDS? Warhol is in a way the spiritual father of AIDS, casual gay sex and equally casual needle-sharing having been daily fare at his Factory. But the cardinal’s cathedral has been made available for a farewell service for the shy, near-blind, bald, gay albino from an ethnic Pittsburgh ghetto who dominated the art world for two decades, hobnobbed with world leaders, and amassed an estate of $100,000,000. He streaked across the sky, a dazzling media meteor, who, in another time or place, could have been a Napoleon or a Hitler.

My face is decorated with huge, haze-crystal earrings. I am dressed for mourning as befits a Superstar, in a dramatic fake Breitschwantz fez and coat, accessorized with black stockings and long, black-laced gloves. I enter through the Fiftieth Street side of St. Patrick’s on the arm of a dear friend, photographer Sheila Baykal, and proceed through the south transept. I am holding a Bible in my hand.

Familiar faces are everywhere, hundreds and hundreds of them. The cathedral seats 2,500; it will be full. The in-town in crowd will not miss this in show for anything in the world.

I am surprised to see a refreshing field of orange and pink tulips and yellow forsythia inside the sanctuary. This abundance of living greenery and sunshine color mellows the rigorous Gothic of the gray stone pillars. A spring celebration appears in order. I did not expect, at this time and place, such joy and abundance of fresh flowers. I rather expected stiff plastic flowers. Plastic is Warhol’s style. Years ago he painted for me unreal, gigantic flowers against a background of fake black grass.

Kneeling in the wooden pew in the second row, to the right of the center aisle, my mascaraed eyes closed, I question my heart for feelings about Warhol.

Did I love Andy?

Yes, for an instant.

Did he love Ultra—the me I was then?

Who knows? It was not about love.

What was it about?

My mind goes back to the sixties, right here in New York. Andy Warhol and Ultra Violet are making news. We are creating—or so it seemed at the time—the most mind-popping scene since the splitting of

the atom. We are living Art in the Making. The press calls it the Pop scene. When Andy died on Sunday, February 22, 1987, the front page of the Daily News, New York’s picture newspaper, screamed: POP ART’S KING DIES.

But wait a minute. I met the King of Pop years ago. His name was Marcel Duchamp.

To me, Andy was the Queen of Pop.

If that is the case, how could I have been his queen?

I was Warhol’s Superstar.

The Warhol world was a microcosm of the chaotic American macrocosm. Warhol was the black hole in space, the vortex that, engulfed all, the still epicenter of the psychological storm. He wound the key to the motor of the merry-go-round, as the kids on the outside spun faster and faster and, no longer able to hang on, flew off into space.

When the storm was spent, when the merry-go-round stopped, the dazed survivors—some of them will be here today—had to grope their way back into an often hostile society. I am one of the lucky sixties people who escaped death, but I have been confronted with my day of reckoning, when my wicked ways had to be abandoned if I was to live at all, let alone in health and sanity.

Lifting my eyes to the vaulted ceiling of St. Patrick’s, I search heaven for meanings. Did the stars incline Andy to be the final master of his destiny? I know—for I once looked it up—that the sun was found to influence his twelfth house at the time of his birth on August 6, 1928, at 6:30 A.M. in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Andy was the sun-at-midnight. The black sun.

Mourners are still filing in. Piano music fills the vast sanctuary, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s “March of the Priests.” I visualize Andy in chromatic ascents and descents in mid-heaven or mid-hell. Amadeus. Andy and Amadeus, parallels of destiny in a fast rise to world fame and an equally abrupt ending, both star-struck with genius and, as such, set apart, blessed, living dissolute existences and dying of negligence.

Andy Warhol, native of a Pittsburgh ghetto, was courted by capitalist patrons of the arts who, in turn, commissioned their portraits to confirm their social status as the Who’s Who of the world. Similarly, Amadeus Wolfgang, native of Salzburg, darling of the court, was appointed imperial composer by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II.

It took only one hour for Andy to make a one-hour movie. Amadeus wrote four violin concerti, each in one day.

Amadeus, a film directed by Czechoslovak filmmaker Miloš Forman, flashes quickly to mind. For a moment I think about the short romance I had with Miloš. But I’m not here to mourn my lost loves. I’m here to commemorate Andy. The mourners have had thirty-seven days since their idol’s death to empty their lachrymal reservoirs. Now no more tears are shed.

How dare I compare Andy to Amadeus? I am comparing their fame. Andy was until just over a month ago one of the best-known American artists alive; today one of the most famous dead. His fame, his influence on art, his body of work constitute a great achievement by any standard. We are all here united to celebrate Andy’s passing. All is forgiven. All is forgotten, remembered no more.

What am I saying? Of course he will be remembered.

Mozart’s music still echoes through the cathedral. His formal themes suggest to me the Warholian formulas. In the popular, materialistic culture of America, Warhol correctly located the center of worship: not Christ on the cross, but Marilyn Monroe on the screen. Irreverently, Andy popped up that image, magnified it, repeated it endlessly.

Marilyn, little Mary, little Mother of God, Marilyn Magnificat, “My soul does magnify the Marilyn …”

Warhol, the high priest, lifting the ciborium, holds up to the congregation the blow-up of the American icon, and they bow their heads in worship of the non-virgin Madonna. (The icon was auctioned for $484,000 at Christie’s in May 1988.) With the same gesture, clothed in the iconic chasuble, image-maker Warhol uplifts himself in front of the populus, which hails him with instant recognition.

From 1962 to 1987, for twenty-five years—not just fifteen minutes—Andy Warhol was famous. More than famous, he was both an acclaimed artist and a potent social force. He changed the way we look at art, the way we look at the world, arguably the way we look at ourselves.

Yet his art only seemed to camouflage the man. One could never know Warhol by listening to him, for he rarely spoke; by reading his books, for he did not write them; by seeing his movies, for he rarely made them himself; by watching him, for he was watching the watchers; by touching him, for he hated being touched.

This was a man who believed in nothing and had emotional involvements with no one, who was driven to find his identity in the mirror of the press, then came to believe that reality existed only in what was recorded, photographed, or transcribed. But he had to have been more than a shadow or a charlatan. Because of him, the glitterati of the world are in church today.

Yet to some, Warhol was only a brilliant con artist who concocted whatever fantasies people needed, a genius of hype and illusion, the ultimate voyeur, who exploited our young people. To others, he was a genuine talent, a genius of the first rank, who held an objective mirror to our plastic society, took America’s faltering pulse, and illuminated the foibles and fixations of our times.

It might be said that Warhol was constantly working the culture to become the male Marilyn Monroe; that was his dream. Hence his fascination with transvestites. Industriously, day and night, he burnished his icon image. The primary creation of Warhol was Andy Warhol himself.

Throughout our years together, I was always asking Andy questions. He liked to be fed questions, although he did not always answer. When he did, his replies were usually brief, brusque, sometimes cryptic; rarely did he speak at length.

“Andy, I think you’re an image builder for yourself and your cause. Is that right?”

“If you say so.”

“What if people worship money?”

“I paint dollars.”

In 1962 Andy painted 80 Two-Dollar Bills, and in 1981 he painted Dollar Signs. Andy knew his market.

“Why do you dress in black leather and dark glasses?”

“James Dean.”

“Where is your imagination?”

“Have none.”

“Why not dress as Popeye, your hero?”

(Because I am French and at that time my English was inexact, I pronounce it Popay. He corrects me and says, “It’s Pop Eye.” Popeye is his childhood hero, Dean his adult idol. Andy reminds me, “Dean said, ‘Live fast, die young, leave a good-looking corpse.’”)

“What do you really want?”

“Instant recognition.”

“By whom?”

“The world.”

Andy got his wish. He became the high priest officiant of taste, glamour, sex, fad, fashion, rock-and-roll, movies, art, gossip, and night life. He was father confessor of the lost kids with all their problems—drugs, sex, money, family. In the confessional, Father Andy, head bowed under his platinum miter, always lent an ear, never listened, just recorded. “Tell me your sins,” he was saying. “I will absolve them.”

“You don’t absolve, you incite,” I accused.

“Ummm.”

“Why do you always let people do what they want to do?”

“Mama always let me.”

I look around St. Patrick’s and see a woman sticking a coke spoon up her nose behind a manicured hand. I close my eyes and hear ostentatious snorting.

The pianist is playing more music from Mozart’s Magic Flute, La Flûte enchanée, Zauberflöte. Yes, Mozartian magic molded the Warhol persona. Magic was a word Andy gargled with for hours. “Magic this, magic that. Figaro sì, Figaro la. Some have magic, some don’t. It’s all magic. Some people make magic, some don’t. It’s just magic. Magic’s the difference.”

Andy was the biggest magician of all.

As a Roman Catholic, Andy worshiped the Church’s magic. In childhood he wore a magical gem, a Czech Urim, sewn by his mother into a secret pocket in his underwear. He sought the power of divination. He sought all power. I remember being told once that New York politicians used t

o call St. Patrick’s the Power House. We’re in the right place.

Andy and power. Maybe that’s why all the girls at the Factory wanted to marry the magical albino. And all the boys wanted to get into his pants.

When Andy put his “Warhol” on, with a mere glance from his nearly blind eyes, things flashed and moved around the room. When Andy, as Disney’s Snow White, donned his pale, wheat-colored wig, the Factory dwarfs, headed by Gerard Malanga, poet and number one helper (at $1.25 an hour), got to work to the sound of a rock-and-roll “Heigh-ho, heigh-ho,” and away we went. Andy was our Dwarf Star. Yes, Andy was right out of the enchanting world of Disney, where instant zap transformed an ugly duckling into a charismatic magician. The reality and the myth were confounded into one.

L’enchanteur enchanté. Andy had a long ancestry of fairy-tale making. When he worked in his youth as a commercial artist for I. Miller Shoes, he revived storybook sketches of Cinderella for an advertising campaign. He wrote, “Beauty is shoe, shoe beauty.” His whimsical drawings of shoes adorned with tassels, cupids, beaded borders, and diamond dust reflected mythic magic.

The art he created is magic realism. Webster’s defines it: “The meticulous and realistic painting of fantastic images.” Magician supreme Warhol, without a wand, struck a Brillo box into a work of art worth $60,000.

Pop goes the weasel! Out of the box, with one ferret and one gimlet eye, one grayish, one bluish, the hybrid albino, a creature of the dark, with a platinum shock of hair, cast a spell; he crystal-gazed at the culture as he translated himself into the conjurer conjured. He uttered his weasel words, “In the future, everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes,” and the members of the audience cheered and applauded, dazzled with the sight of themselves on camera.

Where is Andy now?

Bargaining a portrait of St. Peter for $25,000 worth of indulgences? That’s what his portraits were selling for here on earth. His approach was, I’ll paint anybody for $25,000. All it required was blowing up a Polaroid of the subject, ordering a silk screen, passing a housepainter’s roller with one or two colors across the screen. If you’re wondering where the artistry comes in, it’s all in the concept, not the rendition. It’s the magic.

But St. Peter is not just anybody. In Catholicism he is the keeper of the gate. Andy always wanted to be in, not out. Andy was always concerned about the nobodies and the somebodies. He was so afraid to be a Nobody, so thrilled to be with Somebody.

Famous for 15 Minutes

Famous for 15 Minutes